As he watched the May 27 hearing of the Brazilian Senate’s Infrastructure Commission, Adison Ferreira, co-founder of independent news outlet Carta Amazônia, grew terrified.

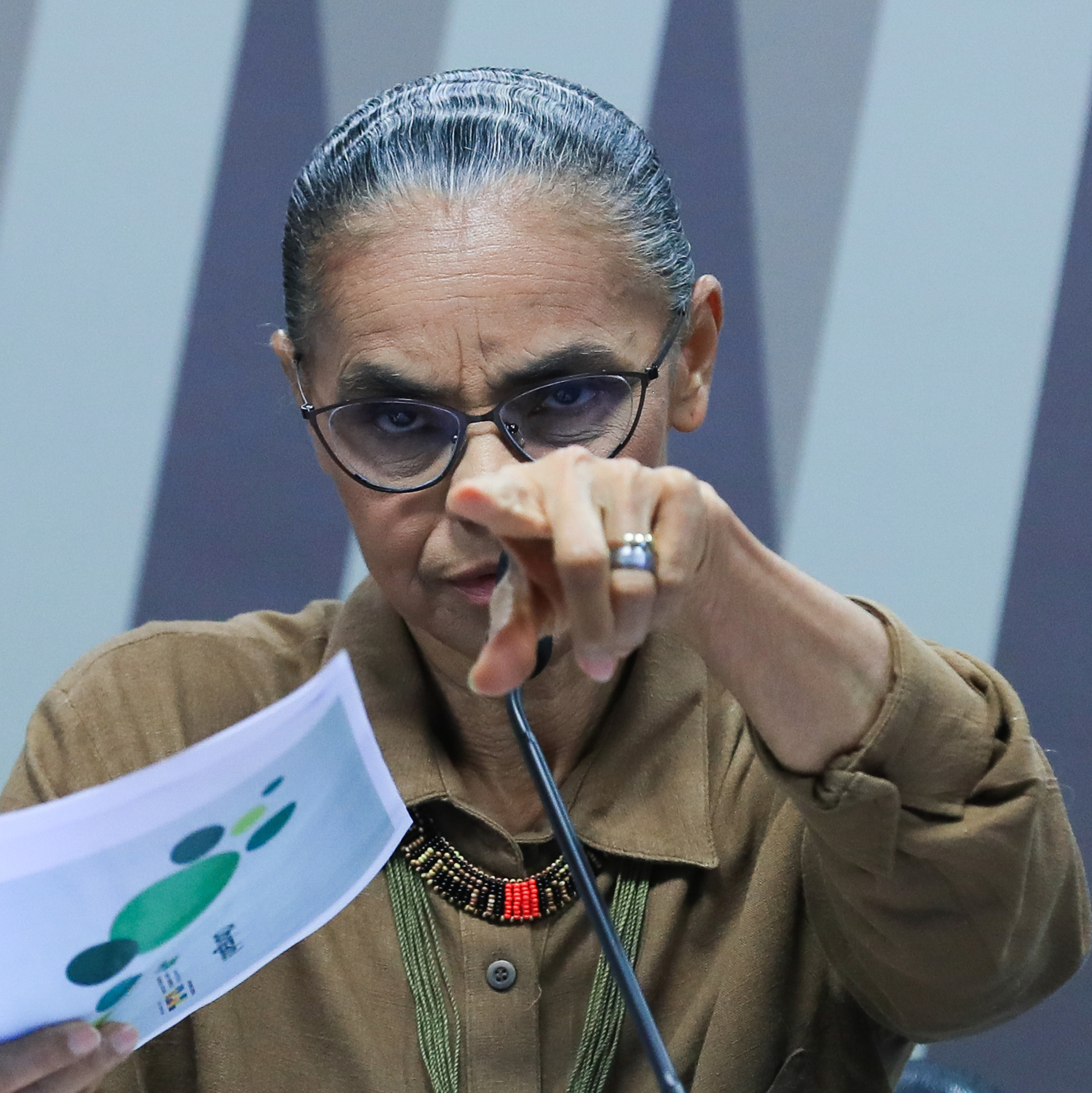

The commission had invited the country’s environmental minister Marina Silva to discuss the creation of new conservation zones in the Amazon. But instead, congressmen used the opportunity to fire a stream of vicious and personal attacks at Silva, who has long been one of the figureheads of the environmental protection movement in Brazil.

One senator told her to “put herself in her place,” another accused her of “hindering the country’s development,” while a third greeted her by saying: “I’m not talking to a woman. Because women deserve respect, but the minister does not.”

After that, Silva demanded an apology. When the senator refused, she departed the hearing.

“I was stunned by the political gender violence,” said Ferreira. “But I understood that attack as much more than just about the minister. The attack was about the environmental agenda as a whole, about defenders of the environment.”

For Ferreira, the episode represented a moment in Brazilian politics and society of extremely aggressive and widespread pushback against the environment. In recent months, Brazilian politicians, supported by huge swaths of voters, have pushed forward a series of projects, laws and executive actions that would each have disastrous impacts on the environment in Brazil, and especially the Amazon.

These measures and the widespread support they have received, have left environmental journalists in the Amazon, who, through their reporting, aim to show the public the catastrophic impacts of destructive projects like these, struggling to maintain hope.

“We even live with a feeling of anguish. It’s really a feeling of helplessness, of ‘my God, where will this stop, where are these things going, how will this all end?’” said Catarina Barbosa, reporter for the independent outlet Sumaúma.

Recently, the Brazilian government has auctioned off 19 parcels for oil drilling at the mouth of the Amazon River, pushed along plans to repave the BR-319, a controversial highway running through one of the most preserved sections of the Amazon, and refused to strike down the Marco Temporal, a legal thesis that claims Indigenous groups only have the right to territories that were in their possession in 1988, the year of Brazil’s constitution.

However, the most devastating blow came earlier this month, with the passage in the Brazilian Senate of a bill that environmentalists have come to call the “Devastation Bill.” The measure would largely hollow out the entire system that governs environmental licensing, allowing projects, such as the BR-319 and oil drilling at the mouth of the Amazon, to be pushed through without legitimate environmental studies. Critics have called the bill one of the most environmentally catastrophic actions since the end of the Brazilian dictatorship in the 1980s, yet so weakened is the environmental movement in Brazilian politics that the measure passed with 54 votes in favor and only 13 in opposition.

Brazil’s progressive president Lula has also refused to oppose the measure and has thrown his full support behind drilling at the mouth of the Amazon and repaving the BR-319.

The success and popularity of these projects reflects the widespread belief in Brazilian society that in order for the country to advance as an economy and elevate its citizens out of poverty, it needs to exploit its natural resources and sacrifice its environmental areas.

“They associate this environmental agenda of the left with poverty, with the low social and economic development indices in Acre, in the Amazon,” said Fábio Pontes, editor of Jornal Varadouro, an independent outlet based in the state of Acre. “The population is led to believe this, that yes, Marina Silva is really to blame for keeping Acre poor, because they say only agribusiness is the best solution for development.”

The stated aim of many of the independent, nonprofit news outlets of the Amazon is to unmask this discourse that connects environmental exploitation to development and show that continued disregard for the Amazon’s protection will result in catastrophic consequences.

For example, independent outlet InfoAmazonia recently published a multi-part investigation of the severe implications of oil drilling at the mouth of the Amazon. Meanwhile, Sumaúma went behind the scenes to report on the Lula government’s inaction and implicit support of the Devastation Bill. And for months, Amazônia Real has reported on the catastrophic and widespread environmental impacts of a paved BR-319.

This kind of reporting is often revelatory, uncovering the economic and political forces behind environmentally destructive projects, measuring the unconsidered environmental ramifications and centering the perspectives of communities that will be most affected. But whether it has tangible impact on the debate over these projects is harder to tell.

“I imagine celebrating the small victories—sometimes my reporting ends up resulting in support for [an environmental case in] the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office, or a project gets postponed in court. Anyway, we celebrate [these impacts] because, overall, things are really quite difficult,” Barbosa said.

This kind of reporting is up against a deluge of misinformation promoting the economic promise of these projects and ignoring their environmental and social consequences spread through social media and by the numerous media outlets funded by politicians and corporations. These information sources are able to reach massive audiences, far larger than those of independent news outlets.

“It’s very hard work because you’re practically alone, often rowing against the tide, many times without support, facing powerful machines, like politicians, agribusiness itself that also finances this kind of campaign, obviously,” said Pontes.

That’s left environmental journalists searching for ways to amplify the impact of their work. Barbosa of Sumaúma recently published an in-depth examination of the socioenvironmental impact of the government’s planned demolition of the Pedral do Lourenço, a rock formation in the Amazon’s Tocantins River. The project, which would allow for cargo ships to traverse the river, has been openly praised by commercial news outlets, but Barbosa showed how it would eliminate local fish populations and therefore the way of life of the surrounding communities.

Barbosa, an experienced journalist who has won several prestigious awards for her reporting, said she often struggles with how to increase the impact of articles like these and reach people who don’t get their news through print journalism.

“How are you going to get the outrage about the Pedral do Lourenço to these people, because they won’t read my article. And that’s okay, no one is saying, ‘Oh, those who read long articles are smarter,’ it’s not about that, it’s about recognizing the audiences, and today audiences are like this,” Barbosa said.

For this particular story, Barbosa sent the article to a TikToker who posts about environmental issues to his over 100,000 followers, who made a video about the story.

“It’s not easy, and we also don’t know what impact [our journalism] is having,” said Pontes. “Will people change their opinion about this? I don’t know, but our objective is at least to expose some narratives and always work with the truth.”

Given the severe economic necessities that lead many in Brazil to believe in this anti-environmental discourse, journalists also must have empathy in order to combat it.

“People in the Amazon are worried about paying their bills. They are worried about having a roof over their heads so it doesn’t rain inside. They are worried about having food on the table,” said Barbosa. “If they need to cut down a tree to put food on the table, they will cut down the tree,” she said, adding that it is the role of the government to incentivize sustainable actions instead of destructive projects.

Jullie Pereira, reporter for InfoAmazonia, agreed. Pereira recently published an article about an operation by Brazil’s environmental protection agency that confiscated hundreds of cattle from illegal farms in an environmental reserve in Acre. In her reporting, Pereira interviewed one of the owners of the farms, who, while crying, told her that he had no other way of making a living.

“What I try to do is to truly keep my ear open, without judging the other person,” said Pereira. “And I think that is really the exercise of listening. The reporter has to know how to listen.”

But having sympathy for the individuals who are searching for economic opportunities doesn’t mean these journalists aren’t outraged at the attacks powerful politicians and corporations have waged against the environment in recent weeks.

“I always use that indignation. I never get used to a situation and I hope I never get used to it,” said Barbosa. “I think in journalism we are very rational. But we cannot lose the ability to be moved.”

Rather than retreating in the face of widespread support for development at the expense of preservation, the independent news outlets in the Amazon have doubled down on their mission to use journalism to defend the Amazon and its communities.

“It’s time for us to act. If we shrink back or resign ourselves to the scenario, then really nothing happens,” said Pereira. “So independent media I see really motivated to cover this theme.”

“I think we are here on the front line, in the trenches, resisting and doing what we can,” said Pontes. “As long as we have energy, we’ll be here.”